People have written to me telling me that one thing they get from my blog is the feeling of being in Chelsea going from gallery to gallery. I think that's great.

Today I'm going to give you the feeling of living in the New York City metropolitan area.

Due to parental type things I left my house at 6:30. Now, there are three basic ways to drive into Manhattan from New Jersey. For the moment we'll set aside the obvious question "What are you doing driving into Manhattan?" If you are dumb enough to want to drive from New Jersey into Manhattan, you've got three choices. The George Washington Bridge takes you far, far uptown. 179th Street, actually; Chelsea starts down around 29th Street. 150 blocks is a fairly long way (Google guesses it's about 9 miles; my mother always said 14 blocks is a mile, so that sounds about right). If you need to get closer to midtown you can take the Lincoln Tunnel which gets you in at about 34th Street. Finally, there's the Holland Tunnel, which lets out near Canal Street, about 30 blocks south of the Lincoln Tunnel; thanks to New York's amusing geography, this is not actually 4th Street.

I live just about straight across from the George Washington Bridge. For fun sometimes I like to drive over to the New Jersey side at night and walk across. Some days I drive over the bridge to get to Manhattan, but if I'm going to Chelsea I have to cover those 150 blocks somewhere, and sometimes there's traffic on the Manhattan side. Meanwhile the trip down to the Lincoln Tunnel, on the Jersey side, is pretty uneventful.

No matter what you do, though, unless you're driving at three in the morning, you're going to sit in some amount of traffic. The question is -- the thing that makes the drive so entertaining -- how much traffic, and can you avoid the worst of it? Knowing this, every New York radio station which has a traffic report, and most do, ends the report with the bridge and tunnel numbers. What's the delay getting into and out of New York at each?

Thus it was that I was listening to the radio as I pulled up to the unmoving wall of cars leading, eventually, to the Lincoln Tunnel. The radio announced that getting in to New York at the Lincoln was an hour, but the Holland was only twenty minutes. Just before the wall of cars is the exit to turn off and head down to the Holland, so I whipped over to the right and shot down towards what I assumed would be the faster route.

What the traffic report did not tell me was the reason the Holland Tunnel was nearly traffic-free. There were no cars at the tunnel because everyone was sitting in traffic a mile or so outside of the tunnel where construction had dropped the road down to one lane. The approach to the Holland Tunnel, too, is one of those beauties of civil engineering: A walled-in covered highway with no exits. Once you're there, you're trapped. I have no idea how long that stretch of road is, but I've sat on it for many an hour, including now an additional hour or so after Thursday night.

When I finally I reached Manhattan and was working my way through the maze of streets to get uptown I looked forlonly at my list of openings. I had five shows I wanted to make it to that night alone, to say nothing of the other eight shows I'd been hoping to see if I had time and the galleries were open. Gallery openings traditionally run from 6 to 8 pm and here it was 7:55. I therefore reduced my list to two: I'd try to see the Clayton Brothers at Bellwether and Double Take at Schroeder Romero.

At almost exactly 8:00 I slowly drove by Bellwether. There was no parking within two blocks. That solves that dilemma. I drove up to Schroeder Romero.

I didn't read any of the materials along with this show so I'm not sure what the theme behind it is; I'm guessing since the name is "Double Take" and it's all photographs that the theme is as simple as "pictures of weird stuff." Actually, thinking on it, I'm going to say the theme is photos which turn out, on close inspection, to be different from what you thought they were.I'm not usually a big fan of photography as art. I'm ambivalent about it. Intellectually I have to, for consistency's sake, say that photography is as capable as any other medium of supporting true art. Practically, though, I think photography is very, very difficult. I also think, when I'm feeling cynical, that most photographers are failed painters. In fact when I was working for Robert Farber I said as much to him; I was somewhat abashed when I found out later from an article that he did actually start out as a painter.

I think the real appeal of photography, the thing that makes it interesting to me, is the fact that a photograph records an actual moment in time. A photo says: This person stood in this spot in this way at this distance from this piece of film at this precise moment. I have a cache of home movies on 8mm and 16mm film my grandfather took in the 1940s, '50s, and '60s, and watching them the whole idea of photography hits home for me: This strip of film was moving through a camera while my grandmother was standing in front of it over forty years ago.

Of course filmmakers and photographers have been subverting this idea one way or another for almost the entire history of photography. Today's digital technology only makes it less applicable. But to me, ultimately, it's still the thing that makes photos worth looking at. Even staged photos depict an actual event, namely the staging of the photos.

And, really, I like photos. I respect photographers and their craft. I've known a number of photographers and I've done some time in darkrooms myself. In the end, I'm not sure that photography is art, but I do like it.

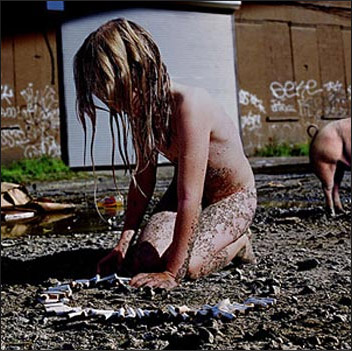

So "Double Take" is a collection of photos which, when you look closer, turn out to be something different than you were expecting. But the most striking photo in the gallery, Untitled #90 by Simen Johan, doesn't seem to fit this description as well as the others. It's certainly strange, and slightly disturbing, but it doesn't turn out to be something of an illusion the way the other photos in this show are. Like many interesting photos, it almost demands that you tell a story about it. But I don't think the story, in this case, is a true one. A dirty, naked child lines up cigarette butts in what looks like a run-down industrial neighborhood; off in the background we can just make out a pig leaving the frame. This could almost be one of those "look at the squalid living conditions in the Third World" photos we see so much of, except it isn't. Is it?

So "Double Take" is a collection of photos which, when you look closer, turn out to be something different than you were expecting. But the most striking photo in the gallery, Untitled #90 by Simen Johan, doesn't seem to fit this description as well as the others. It's certainly strange, and slightly disturbing, but it doesn't turn out to be something of an illusion the way the other photos in this show are. Like many interesting photos, it almost demands that you tell a story about it. But I don't think the story, in this case, is a true one. A dirty, naked child lines up cigarette butts in what looks like a run-down industrial neighborhood; off in the background we can just make out a pig leaving the frame. This could almost be one of those "look at the squalid living conditions in the Third World" photos we see so much of, except it isn't. Is it?

Another interesting photo asking for a story is Pink Bathroom by Carlos and Jason Sanchez. A young person -- boy? girl? -- looks apprehensively from around the corner of the bathroom. At first the scene seems relatively normal. Then you notice, down in the bottom of the photo, the floor of the bathroom, which is dirty, with a rumpled towel, and some broken shower rings from the torn curtain. What's going on?

Another interesting photo asking for a story is Pink Bathroom by Carlos and Jason Sanchez. A young person -- boy? girl? -- looks apprehensively from around the corner of the bathroom. At first the scene seems relatively normal. Then you notice, down in the bottom of the photo, the floor of the bathroom, which is dirty, with a rumpled towel, and some broken shower rings from the torn curtain. What's going on?

Of course there are no answers. These photos are intriguing precisely because you want to be given an answer and there isn't one. You have to invent your own story for them.

The other photos in the show are more firmly doubletakes but not as engaging. Wendy Small has a large beautifully red photogram of what look like alien plants or sea anemones but which turn out to be French ticklers (she smirkingly calls them Freedom ticklers on her site). Caroline McCarthy has a photo of what looks like a fruit still life but the fruit is all sculpted out of wet toilet paper. Alison Jackson is even more heavy-handed: She has a George W. Bush lookalike using Michael Moore and Osama bin Laden photos for target practice; she has an Elton John lookalike getting an enema. If the social commentary were any deeper, I'd need a shovel. You can see the rest on the Schroeder Romero Website, but I wasn't excited by it.

While you're at the gallery, though, you might wander into the side room and see some other good stuff they've got there. Janice Caswell has a neat construction of pins and beads strung together by an ink latticework drawn on paper; Laurie Hogin has a funky, eye-poppingly colored painting of a hairy monkey-like critter sitting on a skull; Jaq Chartier has a few pieces reminiscent of DNA lab results from his series Sun Test.

All in all, the show is worth the trip, especially if you can, like I did, stop in Plus Ultra next door and see Joe Fig's amazing sculptures again. The two galleries have a good thing going: With their openings staggered, it's like they each get two openings for their shows. I like being able to see a show after the opening -- the second time really lets me get a feel for the work. I'm even a little closer to thinking of Joe's objects as art after getting another viewing.

Well, now I've got a list of shows I wanted to see that's as long as my arm. Alyssa Monks at DFN, Valentina DuBasky at Cheryl Pelavin, Jennifer Coates at Feigen, Stanley Goldstein at George Billis, Toshio Iezumi at Chappell, Anne Thompson at Hudson Franklin, Nicole Eisenman at Leo Koenig, Bodo Korsig at Cynthia Broan, Dawn Mellor at Team, Stephen Wright at Henoch, the Clayton Brothers at Bellwether. I'm going to have to take a day this week and do another gallery slog.

I don't want this to become one of those blogs that just throws out links all the time, but I did find this one link over at

I don't want this to become one of those blogs that just throws out links all the time, but I did find this one link over at

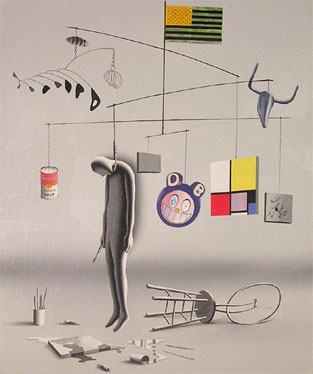

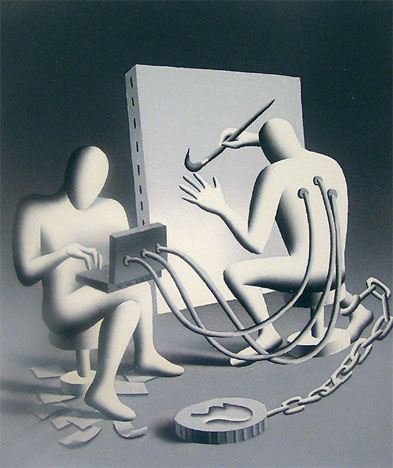

Douglas and I both agreed that our favorite painting in the show is "There's No Place Like Home." Mark said that most people seemed to like "Suicide By Modernism." My guess is that's because people like paintings which quote other paintings; it makes them feel smart to recognize them. And to me the most telling painting in the show is the tiny "Chain of Desire." Mark explained it to us after adjusting the painting below it so it was hanging straight. (I don't think I've ever seen anyone touch an artwork at a show before, and even though I knew it's Mark's show and Mark's painting, I still found it unnerving.)

Douglas and I both agreed that our favorite painting in the show is "There's No Place Like Home." Mark said that most people seemed to like "Suicide By Modernism." My guess is that's because people like paintings which quote other paintings; it makes them feel smart to recognize them. And to me the most telling painting in the show is the tiny "Chain of Desire." Mark explained it to us after adjusting the painting below it so it was hanging straight. (I don't think I've ever seen anyone touch an artwork at a show before, and even though I knew it's Mark's show and Mark's painting, I still found it unnerving.)

"Here I am, directing this assistant." Mark traced the cables running from the laptop to the back of the painter. "And I've got all this cash here. And he's chained to this penny. See that? I've got the cash, he's chained to a penny. And yet here we both are... in this little black and white painting."

"Here I am, directing this assistant." Mark traced the cables running from the laptop to the back of the painter. "And I've got all this cash here. And he's chained to this penny. See that? I've got the cash, he's chained to a penny. And yet here we both are... in this little black and white painting."

So when we look at the work of

So when we look at the work of ![[Christine Mottau]](/blog/images/20060427/christine_mottau.jpg) It turns out Christine Mottau is something of an Abstract Expressionist. She paints fairly large. I'm going to guess about five feet high. On this Christine brushes her colors into shapes with vague intimations of natural forms; ultimately, I think, the forms suggested say more about the viewer than the viewed (I tended to see hips, breasts, flowers and trees -- no surprise there, given my predilections). Her pigments are muddy and strokes tentative at best. I'm not sure, on the evidence of these paintings, that Christine knows what she's doing any more than we do. I picture her in a trance while she paints. I don't consider this a flattering impression. The actual images reminded me very strongly of the cover illustrations of some of the old Dungeons & Dragons modules -- and not the good ones by Trampier or Erol Otus.

It turns out Christine Mottau is something of an Abstract Expressionist. She paints fairly large. I'm going to guess about five feet high. On this Christine brushes her colors into shapes with vague intimations of natural forms; ultimately, I think, the forms suggested say more about the viewer than the viewed (I tended to see hips, breasts, flowers and trees -- no surprise there, given my predilections). Her pigments are muddy and strokes tentative at best. I'm not sure, on the evidence of these paintings, that Christine knows what she's doing any more than we do. I picture her in a trance while she paints. I don't consider this a flattering impression. The actual images reminded me very strongly of the cover illustrations of some of the old Dungeons & Dragons modules -- and not the good ones by Trampier or Erol Otus.  Miki's paintings didn't knock me for a loop the way some Op Art does; their effect is more subtle, like an optical illusion. A very subtle optical illusion which only moves a little bit, out of the corner of your eye. Her work is about contrasting color and clashing, curvy lines. It's all executed so carefully, though, that what reads at first as overwhelming movement quickly shows itself to be very stolid. The varying contrasts of Miki's tones read almost like a Munsell scale. Looking more closely, you can see a texture to her paint, tiny brushstrokes at times working with and then at times against the curves of the composition. This works with the gloss of the paint to lend each painting a shimmery quality in addition to the shivery feeling of the colors and shapes arguing.

Miki's paintings didn't knock me for a loop the way some Op Art does; their effect is more subtle, like an optical illusion. A very subtle optical illusion which only moves a little bit, out of the corner of your eye. Her work is about contrasting color and clashing, curvy lines. It's all executed so carefully, though, that what reads at first as overwhelming movement quickly shows itself to be very stolid. The varying contrasts of Miki's tones read almost like a Munsell scale. Looking more closely, you can see a texture to her paint, tiny brushstrokes at times working with and then at times against the curves of the composition. This works with the gloss of the paint to lend each painting a shimmery quality in addition to the shivery feeling of the colors and shapes arguing.

I believe that any work of art can be placed into one of three categories. After my many years of art experience, I have carefully worked out precise and descriptive terms for each of these three categories, and they are as follows: Wow!, Yuck!, and Huh?. Julie Allen's work is firmly in the last of these. I can't even formulate a decent opinion on her work because I really just have no idea what or how to think about it. This show consists almost entirely of articles of food replicated in sewn fabric. That's right: Julie has created a hamburger on a bun -- with onions! -- out of sewn and embroidered fabrics. Also a banana split, some cakes, little green peppers, mushrooms, salmon steaks, bacon, cherries, oranges, and who knows what all else.

I believe that any work of art can be placed into one of three categories. After my many years of art experience, I have carefully worked out precise and descriptive terms for each of these three categories, and they are as follows: Wow!, Yuck!, and Huh?. Julie Allen's work is firmly in the last of these. I can't even formulate a decent opinion on her work because I really just have no idea what or how to think about it. This show consists almost entirely of articles of food replicated in sewn fabric. That's right: Julie has created a hamburger on a bun -- with onions! -- out of sewn and embroidered fabrics. Also a banana split, some cakes, little green peppers, mushrooms, salmon steaks, bacon, cherries, oranges, and who knows what all else.

On the same floor as those two galleries I found

On the same floor as those two galleries I found  I also wandered into

I also wandered into

By way of contrast, Stux is showing

By way of contrast, Stux is showing  My last stop was at

My last stop was at  Now this is a cool show. What's better than chicks with dicks? Also, this show attracted probably the best-dressed visitors of any show I've seen. One woman turned everyone's head; if she'd been wearing less, it probably would have been less indecent. I heard one guy say to another that she was the model for the fountain. If so, I suspect Paul took some liberties with the genitalia. But you never really do know, do you?

Now this is a cool show. What's better than chicks with dicks? Also, this show attracted probably the best-dressed visitors of any show I've seen. One woman turned everyone's head; if she'd been wearing less, it probably would have been less indecent. I heard one guy say to another that she was the model for the fountain. If so, I suspect Paul took some liberties with the genitalia. But you never really do know, do you?

Paul's paintings are pretty excellent. I wish the reproductions online were in higher resolutions; you really can't see how detailed his little figures are, or how well executed. Paul nicely merges abstract patterns with his figuration. I'm not sure this breaks new ground -- I seem to be seeing a number of painters using a sort of figure-against-flat-background thing -- but it's done well enough to evince a chuckle or two, and it's even a little surprising. His sculptures are well-made, but a little heavy-handed for my taste. Still, a urinating fountain -- while not the most original idea of all time -- is always entertaining.

Paul's paintings are pretty excellent. I wish the reproductions online were in higher resolutions; you really can't see how detailed his little figures are, or how well executed. Paul nicely merges abstract patterns with his figuration. I'm not sure this breaks new ground -- I seem to be seeing a number of painters using a sort of figure-against-flat-background thing -- but it's done well enough to evince a chuckle or two, and it's even a little surprising. His sculptures are well-made, but a little heavy-handed for my taste. Still, a urinating fountain -- while not the most original idea of all time -- is always entertaining.