Last night I attended the opening of Why the Nude? at the Art Students League of New York. The Art Students League is one of those New York institutions I should probably know more about, since I grew up in New York, after all, but which I'm almost totally ignorant of. When you live here, you take a lot of things for granted. One of those things is that you'll hear venerable institutions mentioned in literature and films, and even walk by them on the street, and never once find out what they really are or why they're there.

It turns out the Art Students League is one of those classic New York piles of rock in midtown, with the giant wooden railings and worn steps and floors tiled in tiny squares by craftsmen a hundred years ago. The stairwells have officious letter-sized printouts warning that writing -- "or tagging" -- in the hallways is against policy and anyone caught doing so will be summarily thrown out. So much for the "students" in "Art Students League" -- I've never seen an art school (or any area where artists congregate) that wasn't covered in a gleeful array of scribbles, splotches, and general crap. Even in Paramus, New Jersey, that bastion of middle-class conformity, even there the stop sign nearest to the local Pearl Paint is papered with an incomprehensible melange of weathered stickers. Apparently whatever notions I had of the Art Students League being some outlaw organization forming a safe haven away from the iron gaze and steely fist of the Art Establishment are inaccurate; apparently the Art Students League had, at some point, calcified into its own establishment.

That said, let's talk about the show. I want to get this out of the way early: If you have an even passing interest in the representation of naked humans in art, you should go see this show. The curator -- whose name I cannot ascertain at the moment -- has collected a large assortment of paintings and a few sculptures (and, alas, one video) all related to the subject of the nude. The art here ranges from the mid-1960s all the way to the present and encompasses various approaches; although paintings of the realistic nude predominate, there is one lone quasi-Cubist painting, some drawings, a few photos, and a couple of other unclassifiable things.

Now I'd like to complain a bit. This is so I can end the review on a positive note, not because my complaints are major. It may be that I'm getting jaded, or maybe just crotchety in my old age, but a couple of things bothered me about the show.

The first problem was no one knew who the artists were. I went to the opening hoping to meet artists, in particular Sharon Sprung. No one who worked in the gallery -- not the young women handing out wine, not the person at the information desk -- could tell me if the artists were present, let alone who they were. Granted that a show of this size -- I'm not sure how many artists were represented, but I'm willing to guess about forty -- makes it hard to tell who is who. Still, if you're going to have gallery staff, you could at least introduce them to the artists so they know them.

So I didn't meet even one of the artists, which is a shame. Figuring I was there to meet artists, I decided just to start talking to people. One woman arrived wearing a smock with paint all over the front -- I guess she came in from her studio somewhere else in the building -- and I tried to talk to her, but she brushed me off. Maybe she's tired of weird guys trying to pick her up at galleries. I did speak to one young man taking classes at the Art Students League; he was able to tell me that Costa Vavagiakis, who I desperately wanted to meet after seeing his painting, wasn't around, because this young man is in Costa's drawing class. Costa, he said, is a demanding teacher, but good. Then the young man moved away, possibly because he's shy, but maybe because he, too, is tired of weird guys trying to pick him up at galleries.

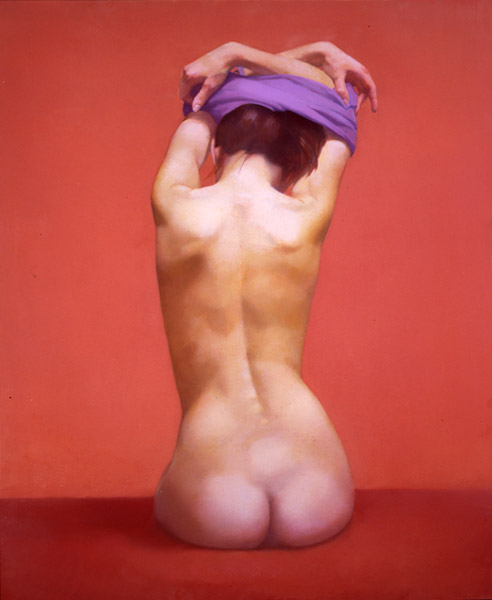

The other problem is the handout at the door is hopelessly limited and the Website similarly devoid of useful material. The brochure clearly tilts towards realism, with the signature piece being Sharon Sprung's R Undressing, and moreover it lists only seven artists out of the more than forty participating. This oversight forced me to actually take notes, something I have not done in the entire time I've been writing reviews. On the positive side, the free Art Students League catalog has reproductions of a few of the good paintings in the show along with a decent sample of what the school has to offer.

The other problem is the handout at the door is hopelessly limited and the Website similarly devoid of useful material. The brochure clearly tilts towards realism, with the signature piece being Sharon Sprung's R Undressing, and moreover it lists only seven artists out of the more than forty participating. This oversight forced me to actually take notes, something I have not done in the entire time I've been writing reviews. On the positive side, the free Art Students League catalog has reproductions of a few of the good paintings in the show along with a decent sample of what the school has to offer.

There. The complaining is now mostly over with. On to the art.

R Undressing is the signature piece of the show, gaining pride of place both on the cover of the show brochure and as the first image illustrating the show online. It's also likely to be one of the first paintings you see walking in to the show. And of course it's why I was there, or anyway Sharon Sprung was. I've seen R Undressing several times now down at Gallery Henoch and it's very striking. I think the feelings of heft and volume are its main attraction, but the contrasting color choices -- the figure tends to the yellow side, with the background being a vibrant warm pink tone -- are also appealing. When I saw it with Stephanie Jackson, I mentioned I liked it although it reminded me strongly of a Boris Vallejo painting, both because of the model's musculature and the colors; Stephanie said, "Who?"

I'd hazard to say there were better paintings in the show, but certainly Sharon's work is one of the best. Some paintings jump out at you from across the room; some sneak up on you. R Undressing is one of the ones that jumps out. Anywhere in the room and it would've had a small crowd around it.

By way of contrast, and illustrating my point, right next to it hung Pink Cushion by Joan Semmel. I didn't even notice it until I'd gone around the room once, but when I did notice it, I nearly wept. It's not that the painting is beautiful and it's not that it's so well painted in a technical sense; it's that, when you really look at it, it shows a warmth and love for its subject (it's a self-portrait, by the way) that is deeply moving. So many of the paintings in this show are perfect examples of academic nudes at their highest expression of the perfectability of man; though it's clear the curator tried to mix in some intentionally warts-and-all depictions. Joan Semmel has found, not a middle ground, but a higher plane, where she's depicted an imperfect body in an imperfect way but with such sympathy and care that the true meaning of what it is to be human comes through. At first glance Joan's subject is just a nude woman; if you stand in front of it, though, it slowly unfolds that her subject is older, with her skin beginning to sag, her breasts droop, her veins show. And yet she's still beautiful. We don't get to be young forever, but there's a certain joy to be found in accepting that.

Bouncing around to the other end of the painting spectrum, turn the corner to find a giant Will Cotton painting, Cotton Candy Cloud (from 2006, not one of the earlier ones). Will's painting seduces you entirely whether you want it to or not. It's enormous -- the reclining woman is almost life size -- and pink and soft. The cloud of, yes, cotton candy is luxurious and inviting, and the nude woman sitting in it equally so. She looks out at you with partly-closed eyes, clearly pre- or post-coital, and she's rendered in such numinous, glowing tones as to be irresistable. She's like something out of Vargas, dropped into the early 21st century, less innocent, more knowing. She's the sweet candy of sex: No sweat, no smell, just an explosion of fantasy flavor, and then she's gone.

I can imagine that a painting like this automatically turns some people off. The forthright temptation of the painting, its obvious desire to be loved -- Cotton Candy Cloud fairly slinks across the room and sits in your lap purring -- might immediately irritate some viewers. But I fell for it the same way I'd fall for a pretty girl hawking a crappy cell phone plan.

Sometimes you have to wonder about placement in these big shows. Right up next to Cotton Candy Cloud is a big charcoal drawing, Reclining Nude by Eric Alberts. I'm not sure this drawing would look good in any context -- this is one of those times where I think, "Damn, why aren't my drawings in a show already?" -- but next to Will Cotton's work, Eric's drawing looks like the largest restaurant placemat doodle of all time. I imagine a curator wants to establish some kind of rhythm for visitors as they walk around, but just so you know: Good/Bad is not the kind of rhythm to aim for.

But you can scan past the drawing quickly and get to the painting which is pulling viewers from around the room, Ephraim Rubenstein's Sarah Pregnant. The most striking thing about this painting is that it's round. But a round painting in a rectilinear show is like a woman wearing a low-cut dress to the theater: Once they catch your eye, you may still find they're ugly. Not in this case, though. Sarah Pregnant is a pretty painting, a wonderful love letter from an artist smitten with his model. It is also, as the note next to the painting explains, the first of many paintings of the artist's son.

What struck me most about the painting was Ephraim's style. Most realistic painters choose one of two styles: Either they try to efface their brushstrokes leaving only smooth tones; or they glorify their brushstrokes in quasi-Impressionistic fervor. Ephraim paints the road less traveled: You can see his strokes, they're part of what gives his subject its texture, but they're subtle with almost no impasto. His tones aren't completely blended, but mix on the canvas; and yet the style is more finished than you'd see in, say, Manet. And the paint is laid on lightly -- you can see the translucent edges of his brushstrokes, sometimes down to the canvas primer. Ephraim's light touch makes the painting seem effortless, like an upbeat gospel song compared to the heavy organ works of most realists.

Speaking of impasto, you can go down the line -- don't worry, we'll back up in a minute -- and see the other extreme, of a painter so in love with paint and its texture that he can barely contain himself. Or he's insane, I'm not sure which. Philip Lawrence Sherrod's JOANN'S*..-(RED*NAILS!)"?,_ -- yes, that's the title, as closely as I could copy it -- is a riotous mass of snaky brushstrokes in wildly mottled colors, all swirling around, with sticky-looking peaks and deep runnels, all energetically focused on Joann's quivering twat being held open by the eponymous red-painted fingernails. I would be amazed if Philip did not immediately fuck Joann silly upon finishing this painting; in fact, I'm guessing he stopped several times before the thing was done just to give her a quick jump. There's an element of ugliness to this painting which just makes it better -- sometimes, you want your sex nasty.

All right, now that you're ogling the other gallery goers with more than passing interest, let's back up to that painting we passed. It's easy to walk by, because when you've got Will Cotton on one wall and Philip Lawrence Sherrod on another, one academic nude starts to look like another. But this one -- ah, this one is different.

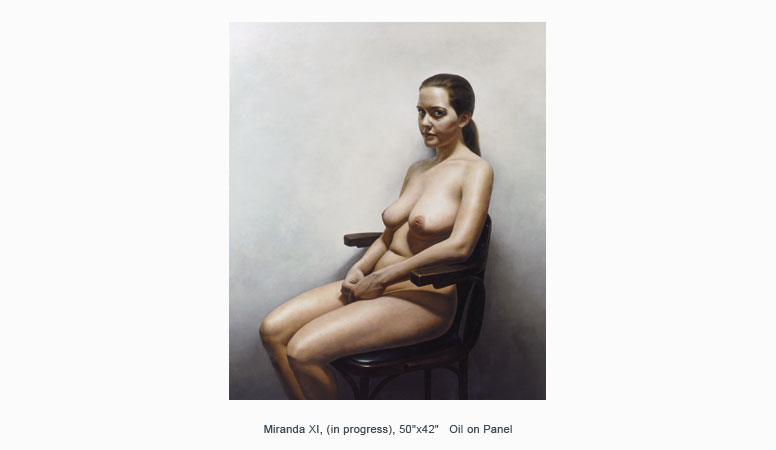

This one is Miranda XI by Costa Vavagiakis, he who I mentioned earlier as being a demanding instructor of drawing. I could have told you he'd be demanding because you can see it in his painting, which shows an absolute mastery of painting technique only achievable through countless hours of practice. As my beloved Professor William F. Ondrick used to say, "There's no substitute for the work. Not even genius." If Costa doesn't have that on a plaque over his door, he has it engraved on his heart.

This one is Miranda XI by Costa Vavagiakis, he who I mentioned earlier as being a demanding instructor of drawing. I could have told you he'd be demanding because you can see it in his painting, which shows an absolute mastery of painting technique only achievable through countless hours of practice. As my beloved Professor William F. Ondrick used to say, "There's no substitute for the work. Not even genius." If Costa doesn't have that on a plaque over his door, he has it engraved on his heart.

This reproduction does the painting no justice at all. For one thing, this image (which is from Costa's site) is of the painting in progress. For another thing, the intense detail is entirely invisible at this resolution. What you cannot see is that Costa has not just painted a portrait of a person, he's painted a portrait of that person's skin. Just about every realist painter I've seen, faced with the difficulty of depicting human skin, throws up their hands and just paints. The texture of the paint ends up substituting for the true texture of skin. Because, look at your skin: It's really difficult to render. It's not one color. It's not even two colors. It's a million different colors, with spots, bumps, shades, hairs, wiggles, creases, veins showing through, folds, ripples -- it's staggeringly complex. Faced with that, even the most obsessive of painters is forced to give up and become something of an Impressionist. Rembrandt -- he whose name is synonymous with absolute mastery of painting -- even Rembrandt just slapped a few pinkish and bluish paints on the canvas and said, "Flesh!" I have often looked at my arm (the most easily examined patch of skin I tend to have around) and despaired at ever depicting human skin in anything approaching a realistic manner. I might even have said it was truly impossible.

Costa Vavagiakis has showed me, however, that it is not. Miranda XI is a perfect rendering of the human body, better than any photograph could ever hope to be. All of Miranda's earthly vessel is here reborn. The subtle blue of veins running beneath her skin. The small nodes around her areolae. The folding of the skin around her knuckles. The curve of her ear. Each pore, each hair, each freckle, everything, it's all here.

And more: Miranda stares out of the painting at us. Most nude sitters are coy -- they avert their eyes, or close them, or are seen from the back. They turn their heads demurely to the side or hide them under locks of hair. Not here. Miranda looks the viewer right in the eye with a defiant air. I want to examine the painting closely, but I feel like I'm inches from Miranda's gaze. She knows I want to look, and she's letting me look, but she's also letting me know that maybe, just maybe, she's not too happy about it.

Miranda XI is the kind of painting that may help a viewer understand why Leonardo's Mona Lisa is the most famous painting in the world. In today's culture it's probably impossible to see La Gioconda with fresh eyes; you've seen the painting reproduced so many times, you know her smile better than you know your own mother's. What made the painting so special is lost in its endless repetition. But I think Miranda XI approaches the same level of art and can give modern audiences a taste of what's so great about a great painting.

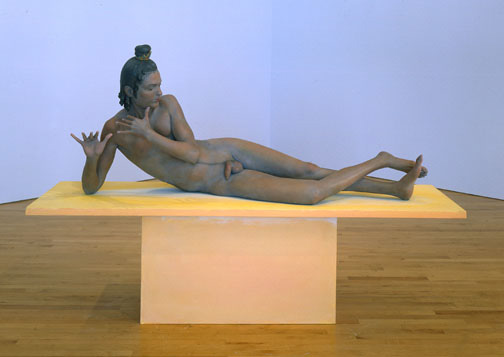

Moving on. Not everything at this show is flat. There are a few sculptures scattered here and there. One of the most enticing is Krishna, by Judy Fox, who is lounging near the middle of the room.

I'd like to be able to say my first homosexual experience was at the Art Students League. But that would be lying. My first homosexual experience was at Boy Scout camp, like everybody else's. However, I came close to having another homosexual experience upon viewing Krishna, because, damn, he's so beautiful. He's lying there unconcerned, calmly posing in some symbolic form, his penis draped casually over one thigh. Oh yes, Krishna is well-hung. I know he's supposed to be pretty, as he's an important Hindu god, but I didn't realize he was so impressively endowed. If more men actually looked like this, I'd consider switching teams. Or anyway switch-hitting.

I'd like to be able to say my first homosexual experience was at the Art Students League. But that would be lying. My first homosexual experience was at Boy Scout camp, like everybody else's. However, I came close to having another homosexual experience upon viewing Krishna, because, damn, he's so beautiful. He's lying there unconcerned, calmly posing in some symbolic form, his penis draped casually over one thigh. Oh yes, Krishna is well-hung. I know he's supposed to be pretty, as he's an important Hindu god, but I didn't realize he was so impressively endowed. If more men actually looked like this, I'd consider switching teams. Or anyway switch-hitting.

Back on the wall, there is Anthony Palumbo's wild Cheese and Crackers. Anthony cheerfully jettisons any attempt at natural coloration or proper drawing to bring forth this wacky painting. I appreciate artists who can use color with imagination; matching colors you can see is difficult, but using colors straight out of your imagination and still making things look right isn't easy, either. Anthony's purples and greens combine to make a recognizable nude in spite of themselves and the result is simply exuberant.

Much more traditional but still vibrant is Standing Nude by Leonid Gervitz. After seeing some of the other work, Leonid hardly looks like the obviously talented painter he is, but what's most arresting about this painting is his Caravaggio-like use of chiaroscuro. That and the cat rubbing against the model's legs.

Finally, on your way out, you might notice a painting you missed coming in. It's right next to the door facing into the room -- facing Sharon's and Joan's paintings, in fact. It is New York Harbor by Robert Neffson. Robert mostly works on city scenes, but in this case he's put someone in front of a vast and detailed buildingscape. His paint handling is in a very different style from many of the more academic artists in this show; he invests more in vivid and sprightly colors. The nude woman strides across the painting in the foreground, pouring water from a bowl into her mouth. There's an air of unforced intimacy in this painting, almost like a snapshot; the woman hides her nudity from outside eyes by holding a cloth draped over her shoulder, but we're on her other side. It's morning in New York and the air feels fresh and clean against her skin, some spilled water drops drying on her arm.

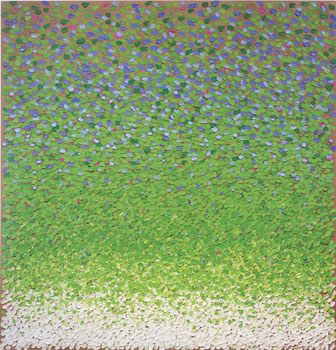

You might leave this show still asking yourself, why the nude? Why indeed? Most of the artists give an answer to this question in the little note cards next to each painting. The best answer may have been given by William Scharf -- whose painting, ironically, isn't even recognizable as a nude -- who wrote, "Why the nude? Why not?"

Mary Henderson is a hyperrealist similar to

Mary Henderson is a hyperrealist similar to  Sometimes the only thing worthwhile about a painting is its technique. Sometimes a painting is good in spite of its technique. In Mary's case, her paintings use technique to convert something which would be boring and pointless -- personal photos of people you don't know doing things you don't care about in places you've never been -- into something almost holy and magical. This is not just a pretty girl sitting in the grass holding her cell phone, which image would be irretrievably uninteresting as a photo unless the girl was my high school sweetheart. This is a young woman suffused in the glow of a beautiful day, captured in a moment of happiness and beauty which belongs to an unreachable past. Somehow, through her intense concentration on the subject, through bringing all of her talent and experience to bear on the execution, Mary has imbued this simple scene with more emotive strength than a thousand photos.

Sometimes the only thing worthwhile about a painting is its technique. Sometimes a painting is good in spite of its technique. In Mary's case, her paintings use technique to convert something which would be boring and pointless -- personal photos of people you don't know doing things you don't care about in places you've never been -- into something almost holy and magical. This is not just a pretty girl sitting in the grass holding her cell phone, which image would be irretrievably uninteresting as a photo unless the girl was my high school sweetheart. This is a young woman suffused in the glow of a beautiful day, captured in a moment of happiness and beauty which belongs to an unreachable past. Somehow, through her intense concentration on the subject, through bringing all of her talent and experience to bear on the execution, Mary has imbued this simple scene with more emotive strength than a thousand photos.

The main area was taken up this time by

The main area was taken up this time by  Lurking in the back of Stux I found the works of

Lurking in the back of Stux I found the works of  Next I stopped in

Next I stopped in  Since I was over at that end of the block and its doors were opened, I went in to

Since I was over at that end of the block and its doors were opened, I went in to  Should I like Michael Cheval? Probably not. Do I like Michael Cheval? Hell yes I do. Michael is the painter I wish I was. No: Michael is twice the painter I wish I was. If I could be half of Michael Cheval, I'd take it home and tell everyone I won the gameshow. Is he really that good? No. He's not. Technically he's superb -- technically he's incredible, almost as good as Dalí at his peak. He's not quite as flawlessly smooth, not quite the total master of his media. But he's better than almost everyone else who's ever picked up a brush. Still, his paintings lack a certain something, the same way Dalí's do. They're brilliant, they're beautiful, they're stunning -- and they're embalmed. Chilly. A little stiff. Not in terms of composition or rendering -- oh no, those would be technical weaknesses, and this work has almost none of those. No -- in terms of pure emotion. Van Gogh was sloppy, a mess, his canvases are little and crowded and sometimes even sort of muddy. But they radiate emotion, they're practically vibrating with feeling. Everything that made Van Gogh who he was is encased in every single brushstroke of his paintings. Not so Dalí and not so Cheval: Their brushstrokes have been drained of passion. Michael is an instrument of exquisite subtlety and grandeur, but he's playing an elementary melody. He's a

Should I like Michael Cheval? Probably not. Do I like Michael Cheval? Hell yes I do. Michael is the painter I wish I was. No: Michael is twice the painter I wish I was. If I could be half of Michael Cheval, I'd take it home and tell everyone I won the gameshow. Is he really that good? No. He's not. Technically he's superb -- technically he's incredible, almost as good as Dalí at his peak. He's not quite as flawlessly smooth, not quite the total master of his media. But he's better than almost everyone else who's ever picked up a brush. Still, his paintings lack a certain something, the same way Dalí's do. They're brilliant, they're beautiful, they're stunning -- and they're embalmed. Chilly. A little stiff. Not in terms of composition or rendering -- oh no, those would be technical weaknesses, and this work has almost none of those. No -- in terms of pure emotion. Van Gogh was sloppy, a mess, his canvases are little and crowded and sometimes even sort of muddy. But they radiate emotion, they're practically vibrating with feeling. Everything that made Van Gogh who he was is encased in every single brushstroke of his paintings. Not so Dalí and not so Cheval: Their brushstrokes have been drained of passion. Michael is an instrument of exquisite subtlety and grandeur, but he's playing an elementary melody. He's a  Let's move on to easier things. Like

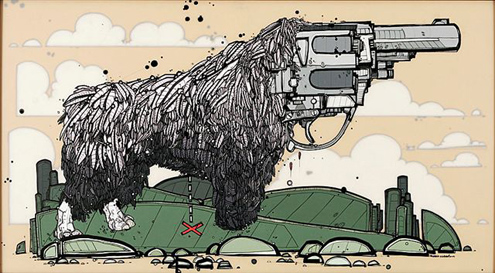

Let's move on to easier things. Like  Only I'm not pleased. Part of the problem is Nicholas' subjects, which are these manga/graffiti-inspired mergings of animal and weapons machinery. What are we supposed to make of these? Bionic penguins? Cyber-chickens? Is there some way to give a crap about them? The other part of the problem is sheer scale: Two or three animal-handgun combos might be mildly amusing and intriguing, but the walls of the gallery are fairly plastered with the damned things. After a few minutes of this repetition, I'm ready to dislike anything Nicholas draws just on principle.

Only I'm not pleased. Part of the problem is Nicholas' subjects, which are these manga/graffiti-inspired mergings of animal and weapons machinery. What are we supposed to make of these? Bionic penguins? Cyber-chickens? Is there some way to give a crap about them? The other part of the problem is sheer scale: Two or three animal-handgun combos might be mildly amusing and intriguing, but the walls of the gallery are fairly plastered with the damned things. After a few minutes of this repetition, I'm ready to dislike anything Nicholas draws just on principle.

And it all really started with Ed and his drawings. Ed's drawings inspired me to doodle a great deal during staff meetings back then and I still love his style, with its strong lines and tribal-tattoo inflection. What Beer Goes with Fish? is an excellent example of Ed's loose, open, doodly, stream-of-consciousness drawing.

And it all really started with Ed and his drawings. Ed's drawings inspired me to doodle a great deal during staff meetings back then and I still love his style, with its strong lines and tribal-tattoo inflection. What Beer Goes with Fish? is an excellent example of Ed's loose, open, doodly, stream-of-consciousness drawing.

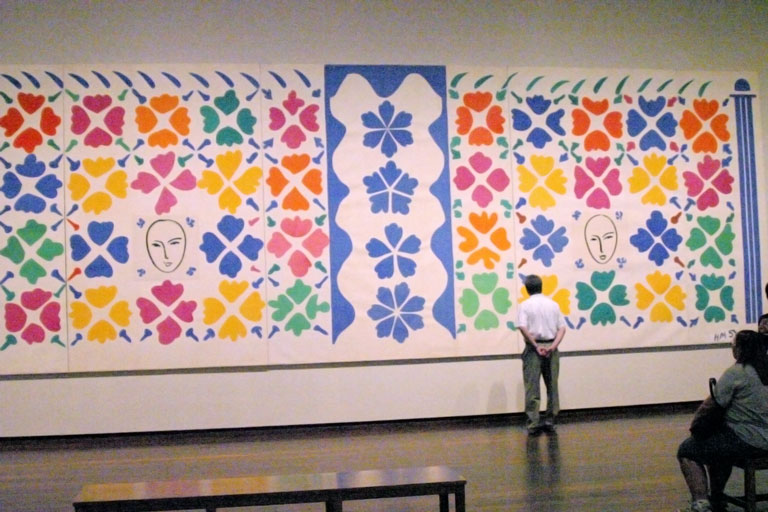

What blew me away was not so much the works themselves, although they're pretty impressive. What really got to me was the realization that draftsmen before me -- that Matisse himself -- had been working on liberating the drawing from the paper. I knew this before, of course -- in the National Gallery there are several examples of

What blew me away was not so much the works themselves, although they're pretty impressive. What really got to me was the realization that draftsmen before me -- that Matisse himself -- had been working on liberating the drawing from the paper. I knew this before, of course -- in the National Gallery there are several examples of