![[Inka Essenhigh]](/blog/images/20060304/inka_essenhigh.2.jpg) You may have seen Inka Essenhigh's paintings before. You may have seen images of her paintings on the Web. But you have not seen what she has now.

You may have seen Inka Essenhigh's paintings before. You may have seen images of her paintings on the Web. But you have not seen what she has now.

Inka Essenhigh has painted a masterpiece.

This measly little image here cannot even hint at how great this painting is in person. I've done a fair bit of gallery-hopping and I've yet to see anything I would say truly belongs in a museum (although I've seen stuff in museums I'm not sure belonged there). Inka's work deserves to be on the same walls as any 20th century artist.

Inka started out painting in a very flat style. In her early works the whole painting surface almost looks enameled. She then populates this with obsessively outlined amorphous shapes which resemble real-world objects but which refuse to actually become whatever you think they are. On closer inspection, there is no closer inspection: Everything dissolves into lines and planes of color.

Over the past few years her work has grown. When I last saw a painting from her, a couple of years ago at one of the big shows on the piers, Inka had added depth and lighting to her work and a much more confident use of paint. It was also much easier to figure out what was actually going on in the painting: "Oh, it's a man packing a suitcase." I didn't think this was a bad thing, but overall the work seemed a little tentative.

Not any more. What Inka has up at 303 Gallery right now is perfectly poised and very powerful. This painting I've reproduced here is absolutely fantastic. I'd say it was about five feet square, so it was impressive just in size alone. The paint is no longer flat; she's allowed herself some brushwork here. I'm not sure if she changed media from her earlier paintings or not, but now she's clearly using oils. The depth she achieves is astonishing given how abstract some of the objects are. And there's clearly something recognizable going on, although there's still room for interpretation.

When she heard I was going to see Inka Essenhigh, my friend Jeanne Brasile -- who's starting as a curator at Seton Hall next week -- asked to come along. She was not disappointed; we were both blown away by this exhibition.

It's a small show. I remember four or five paintings. I got the impression, too, that Inka had rushed out the last painting, which looked less polished and somehow slightly unfinished compared to the others. That, plus a few really large, really blank walls, made me think the gallery had been expecting more. Not that it mattered to me: Any show with just one of the paintings on display here would've been a very good show.

I was lucky enough to grab Inka for a moment to talk to her. I followed right after a young girl, maybe twelve years old, who got Inka talking very graciously about her nearest painting and also had her sign a postcard. I've never seen an artist asked for an autograph before. It was sweet. I mentioned to Inka that none of the paintings were titled or signed and she told me it was all part of the minimalist aesthetic. Beyond that there wasn't much to say other than to heap praise on her, and she's kind of small and I didn't want to bury her, so I let her go back to shaking hands all around.

Jeanne and I couldn't find any postcards ourselves -- I guess we arrived after the big postcard run -- so we hustled out into the freezing Chelsea night and on to our next destination, which was to the Mary Boone Gallery and Brian Alfred's opening there.

Mary Boone's gallery is so cavernous it dwarfs all but the most massive installations. Brian had painted large to fill the space but even so, both the paintings and the number of visitors seemed small and sparse in comparison. This meant I was able to get a really good, long look at his paintings, though, which isn't common at openings; and I could talk to the artist for a good long while.

Mary Boone's gallery is so cavernous it dwarfs all but the most massive installations. Brian had painted large to fill the space but even so, both the paintings and the number of visitors seemed small and sparse in comparison. This meant I was able to get a really good, long look at his paintings, though, which isn't common at openings; and I could talk to the artist for a good long while.

Brian's paintings are extremely flat, like some kind of triumphant return of the 1970s. It was clear looking at them that he'd spent a lot of time cutting friskets and masks, taping off areas of the canvas, before even putting down paint. They're so carefully planned even the edges of the canvas were masked. I always like to see such insanity in an artist; I gave up airbrush because I couldn't take all of the careful masking involved. So I admire anyone who sticks with it.

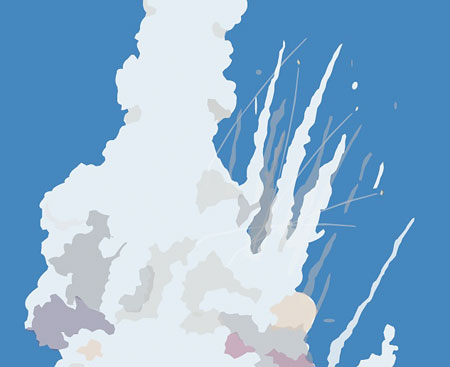

Brian, Jeanne and I spoke specifically about the painting I've reproduced here, "The Saddest Day of My Youth." I didn't pick up on it immediately -- and the paintings were hung untitled -- but it's an image from the Challenger disaster. His parents, Brian said, had the Kennedy assassination. Younger people had September 11th. But he had the explosion of the Challenger, which he witnessed in a school assembly in junior high where they'd gathered to watch the launch on TV. I remember the Challenger well, but at least it wasn't a surprise by the time I saw the news footage. Brian and his classmates got to see it as it happened. We agreed that September 11th was more horrific, of course, but Brian pointed out that the Challenger was destruction of a different kind. When you think of space exploration you think of adventure, excitement -- you don't think of disasters, or anyway you didn't when you were a kid, at least until 1986.

Brian also explained something of how he works. He starts out working on his paintings on computer, adjusting shapes and colors, and when he gets it right he works from that to create the large painting. I could see his friskets overlapped in places, and in one particular spot I could see he'd painted over an area which had been masked off, and he told me that's intentional: He could make everything fit together perfectly, but he'd rather leave the evidence that an actual person painted this. He also leaves himself room to change his mind as he paints, which is surprising since his paintings are so carefully worked out before he starts.

After admiring Brian's paintings -- and the early Essenhigh in the gallery's back room, which provided good insight into how she's progressed as an artist -- and finding nothing interesting in my printout from the Douglas Kelley Show list, we went back to West 22nd to catch an opening we'd heard about from another gallery hopper at Sikkema Jenkins & Co..

Sikkema Jenkins had two openings, one for a group show, "Turn the Beat Around," and one for Kara Walker. The group show had some pretty lousy art -- I found the young girl from Inka's opening staring quizzically at what appeared to be a poorly made prosthetic leg standing in the middle of the room -- and two good paintings, one of which I found an image for and put here. Marc Handelman's "Raptus" was kind of neat. Very energetic and big, kind of wacky. Most of what was on the walls otherwise, and also on the floor, was pure dreck. I didn't even try to find out who did what or why.

Sikkema Jenkins had two openings, one for a group show, "Turn the Beat Around," and one for Kara Walker. The group show had some pretty lousy art -- I found the young girl from Inka's opening staring quizzically at what appeared to be a poorly made prosthetic leg standing in the middle of the room -- and two good paintings, one of which I found an image for and put here. Marc Handelman's "Raptus" was kind of neat. Very energetic and big, kind of wacky. Most of what was on the walls otherwise, and also on the floor, was pure dreck. I didn't even try to find out who did what or why.

In the next room, Kara Walker had some pencil drawings and a video, all uniformly awful. Jeanne protested that the works were supposed to upset me, but I don't think they upset me in the right way; I was just irritated at the crappy draughtmanship and pretension of it all. When the gallery decided it was time to kick the capacity crowd -- including Village Voice art critic Jerry Saltz -- when it was time to kick us out, they lowered the lights, which was really only an improvement. By the time Jeanne and I made it to the front door they'd even turned off the plug-in wall hanging art type thing that was the first piece we saw in the show, and I felt that was probably good for everyone.

Leave a comment